The M7. With every new trove of data comes a mountain of superlatives. Best talent. Best outcomes. Tops in the rankings.

So you have to ask: In what ways aren’t the M7 — the Magnificent Seven business schools, the elite of the elite — the finest in the world? And it’s hard to come up with an answer.

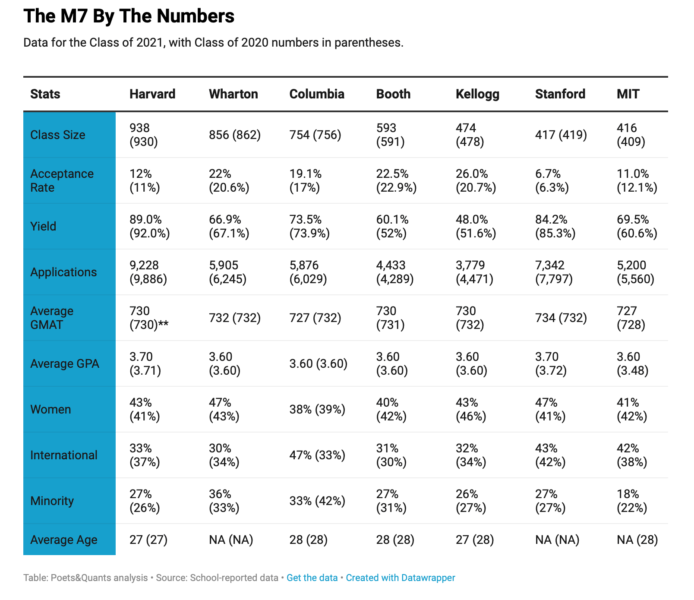

Not by admissions standards. The full-time MBA programs at Harvard Business School, Stanford Graduate School of Business, the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, Columbia Business School, and MIT’s Sloan School of Management are among the hardest in the world to get into. Not in terms of employment results — the all-important ROI. Starting salaries, signing bonuses, and performance bonuses for M7 grads rival or exceed those of any peer school’s MBAs. With the top faculty, pioneering research, constant curricular innovation, networking and employment opportunities, access to capital and influence, permanent hegemony atop the rankings — the M7 schools are where the action is, and everyone knows it.

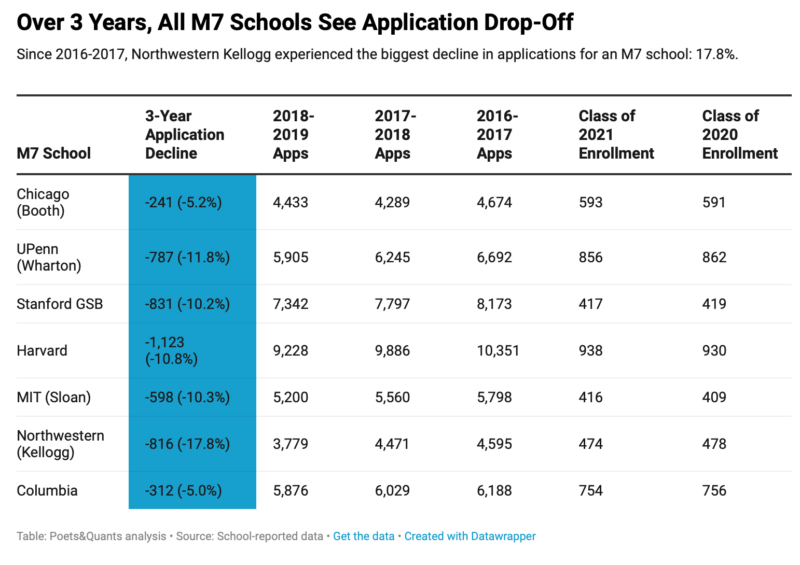

Of course, it all comes at a huge price. An MBA from any of the M7 schools will set you back more than $200,000, not counting two years of lost income — among the priciest two-year educational experiences in the world. Which leads us to the one, main way in which the M7 are currently just as vulnerable as their peers and their mid-tier counterparts: their MBA programs, flagships of each school, are struggling with a shrinking talent pool. (Just as we noted last year.) With a shrinking pool comes side effects like a rising acceptance rate, a falling yield, and the plateauing of other metrics like average Graduate Management Admission Test scores and grade-point averages. All of this is underway now at the M7 schools, with no end in sight.

WHAT IT MEANS TO BE AN M7 SCHOOL

The M7 is not a formal designation. Many years ago, the deans of the seven schools decided to create their informal network to share information and to meet twice a year. Through the years, the group has been limited by the self-anointed seven institutions. But it’s not only the deans who get together. The M7 modality cascades down to meetings among vice deans, admission directors, career management directors, even PR, and marketing types.

At the private sessions, for which the schools rotate hosting duties, business school officials trade gossip, best practices, and whatever topical issues end up on the agenda.

There’s a good bit of jealousy about these meetings, especially from the deans of schools just outside the M7, who privately gripe about how elitist the whole exercise is. Poets&Quants plans to look “beyond the M7” in the new year — examining which schools might constitute a “Second M7” or an “International M7,” and which school or schools might rightfully be excluded from the M7 based on recent performance.

From an applicant’s point of view, the M7 continues to be the Holy Grail of the MBA kingdom. Every year, there’s a sizable number of applicants who will only apply to the M7 schools or a subset of them, even though there are many other business schools that are just as or nearly as good. Indeed, for some candidates, a case can easily be made why Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business, or the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business, or Yale School of Management, or one of several other elite B-schools might well be preferable to an M7 institution. After all, the cutoff at seven was arbitrary to begin with and was made at a very different time.

Still, the fascination with this mysterious group and these schools can turn into an obsession for any highly striving MBA candidate. Which is why we’ve put together this comparative look at the M7 players, comparing and contrasting them by everything from SATs and GPAs to starting salaries and job offer rates.

Nguồn bài viết: Poets & Quants